|

It is curious how sounds evoke memories. Cicadas shrilling in the pinyon-juniper woods behind my New Mexico home transport through the decades to another May afternoon and a younger self aboard a 15-foot jon boat, a creel clerk for the Ohio Division of Wildlife. I would spend days roving over a reservoir, conducting in-person interviews of anglers in boats and on shore, gathering information on what they caught, how far they drove, hours they spent fishing, and how many fish they kept in the creel. Catch rates and preferences were useful baseline and trend data for a sauger and white bass fishery.

That spring day the air was stock still, thick like stew. The buzz of bugs floated onto the tranquil water, coming to my ears gentle as a feather, sporadic like waves rising and falling and lightly lapping onto a shoal. Cicadas droned incessantly from the maples and hickories on the hillsides rimming the lake. If sound had color, theirs would be featureless and monochromatic. The thumb-sized bugs were serious about their future. They looked to breed and die in a matter of days. Their offspring would repeat the noisy ritual in 17 years.

Coming upon a pair of anglers aboard a boat with a glittery hull, I killed my burring outboard and walked forward. My boat came to rest. Standing on the bow, I watched the water surface between us turn into a froth in a flurry of feeding fish. A school of white bass made a boil feeding on luckless gizzard shad. The anglers dropped curly tail jigs into the frenzy and took part in the food chain, lifting out slabs of white bass gleaming like sterling silver.

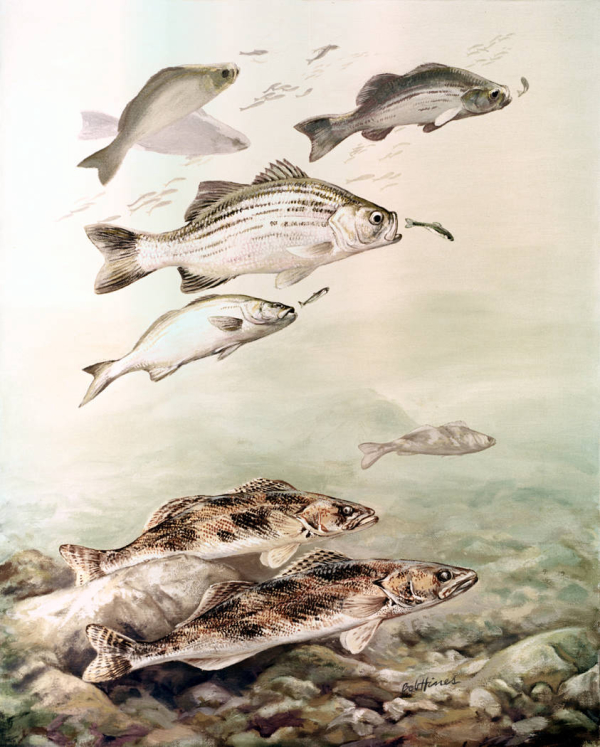

White bass are great fish both on the end of a line and in the skillet. A freshly angled fish looks like polished chrome with a slight bluish-olive tinge somewhat akin to the well-worn bluing of an old shotgun barrel.

Only a matter of mere miles from where my memory takes me, Constantine Rafinesque captured a white bass from the Ohio River on an epic sojourn in 1818. The Turkish-born Kentucky polymath professor of natural sciences, economics, and archeology published Ichthylogia Ohioensis in 1820 and called the fish the “golden-eye perch.” He caught the fish from the Falls of the Ohio near Louisville. The cataract is gone as are the natural long-distant runs of white bass, waylaid now by locks and dams.

But white bass are not uncommon. Using Sport Fish Restoration dollars derived from taxes paid by tackle manufacturers and taxes levied on motorboat fuel, state fish and wildlife agencies manage naturally occurring populations from northeast Texas to Michigan’s upper peninsula. Biologists have stocked white bass in reservoirs where the waters are clear and deep, both within their native range of the Mississippi, Ohio, and Great Lakes basins, as well as into isolated lakes in the West. Sight-feeders like white bass do well in clearer waters where smaller fish are their favored fare.

I spent eight months on the reservoir and interviewed thousands of anglers from all walks of life. Sport Fish Restoration dollars supported it all: my salary, the jon boat, the fuel, paper forms and clipboard, and for the senior biologists and statisticians to analyze the biological and demographic data to inform future fishing regulations and stocking regimes.

Those southern Ohio cicadas have since twice gone through their 17-year-long life cycle. Despite the many summers that have slipped downstream, I vividly recall the bass boil and the two anglers I interviewed after they hauled in several slabs of white bass. They were delighted to participate in the survey—and contribute to fisheries management.

To learn more about Sport Fish Restoration, visit Partner with a Payer.

Advertising

Advertising